The late and famous around the Bay Area

Date: March 25, 2009

Author: Kevin Fagan; Chronicle Staff Writer

Memo:

E-mail Kevin Fagan at kfagan@sfchronicle.com.

Copyright (c) San Francisco Chronicle 2009

Record Number: 0B16MJ57

The Bay Area has more than its share of celebrities, but it’s particularly rich in one class of famous people you’ll never catch a sighting of.

Not above ground, at least.

From the wacky Emperor Norton and baseball legend Joe DiMaggio to the founder of the Ghirardelli Chocolate empire, thousands of the most important figures in the past century and a half of the nation’s history populate crypts, coffins and cremation urns from Oakland to Colma. The mother lode of those graves is the tiny city of Colma, where 17 cemeteries sprawl across an expanse of fields about 5 miles south of San Francisco. Established at the turn of the 1900s as a necropolis to take San Francisco’s dead after city leaders evicted most of the cemeteries, Colma now hosts the remains of 1.5 million people. And 13,000 animals, if you count the Pet’s Rest cemetery for critters.

Among Colma’s permanent residents are DiMaggio and fellow slugger Lefty O’Doul, California Gov. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, assassinated San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, jeans innovator Levi Strauss and sugar king Claus Spreckels. And – again, if you coun t Pet’s Rest – singer Tina Turner’s dog, wrapped in one of the star’s fur coats.

The more-than-a-little bizarre Norton, a.k.a. Joshua Abraham Norton, is also buried in Colma. He was essentially a street bum who declared himself Emperor of the United States, and was benevolently cared for by bemused city residents. When he died in 1880, more than 10,000 people jammed his funeral. Not far from Norton are the graves of true-life newspaper emperors William Randolph Hearst, founder of the newspaper chain that owns The Chronicle, and Charles de Young, original co-founder of The Chronicle.

The San Francisco National Cemetery in the Presidio managed to escape the graveyard eviction craze of the early 1900s, and it features the remains of African American “buffalo soldiers” and Pauline Cushman-Fryer, a renowned spy for the Union Army during the Civil War. Also spared the city’s boot was Mission Dolores Cemetery, which hosts more than 5,000 Ohlone and Miwok Indians w ho helped build the mission in the 18th century.

Across the bay in Oakland, 400-plus victims of the Jonestown Massacre are buried in a mass grave at Evergreen Cemetery, and Mountain View Cemetery is home to famous architects Julia Morgan and Bernard Maybeck, coffee king James Folger and Domenico Ghirardelli. “We certainly do have very interesting people buried up here, but Southern Californians might disagree about which area is more interesting,” said Alison Moore, reference librarian for the California Historical Society. “They have all those Hollywood types down there (i.e., stars at Forest Lawn include Steve Allen, Betty Davis and more).

“We tend to take our cemeteries more seriously up here, though,” Moore added. “Maybe that’s the big difference.”

Serious or not, like their living counterparts, the Bay Area’s deceased celebrities got plenty of ink in The Chronicle when they met their ends – and they get plenty of visitors to this day. Take the best-known local underground celebrity of all: Wild West hero Wyatt Earp.

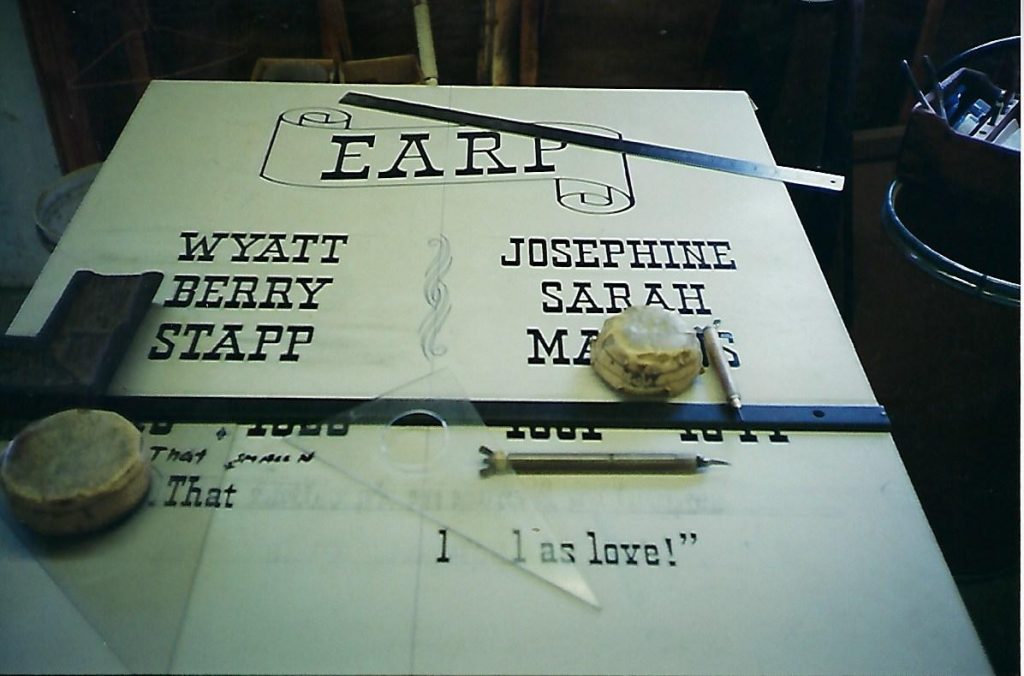

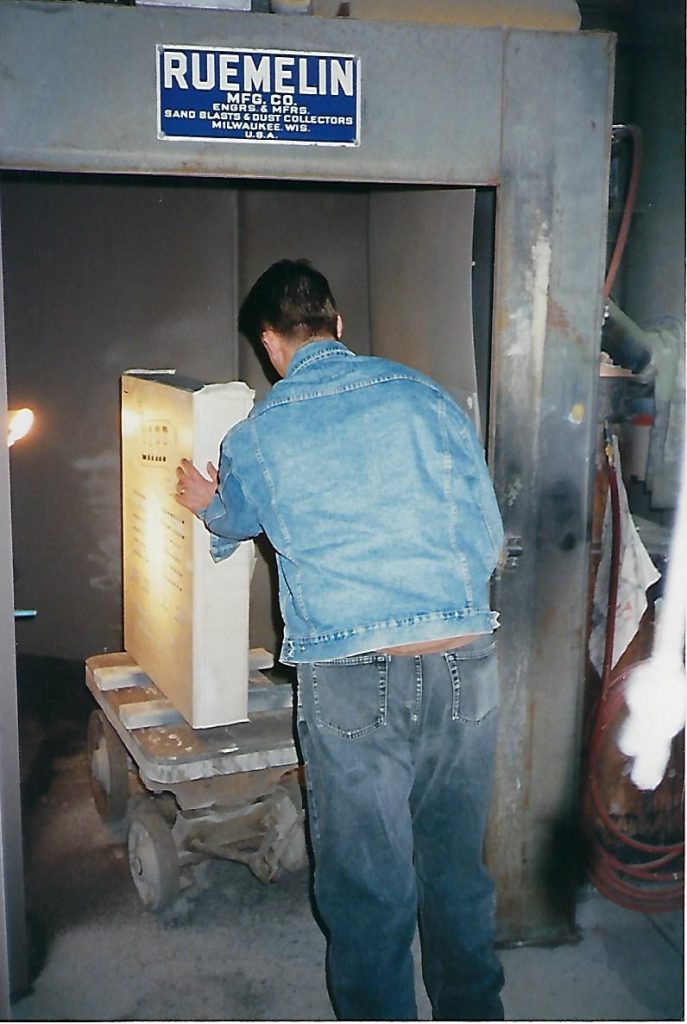

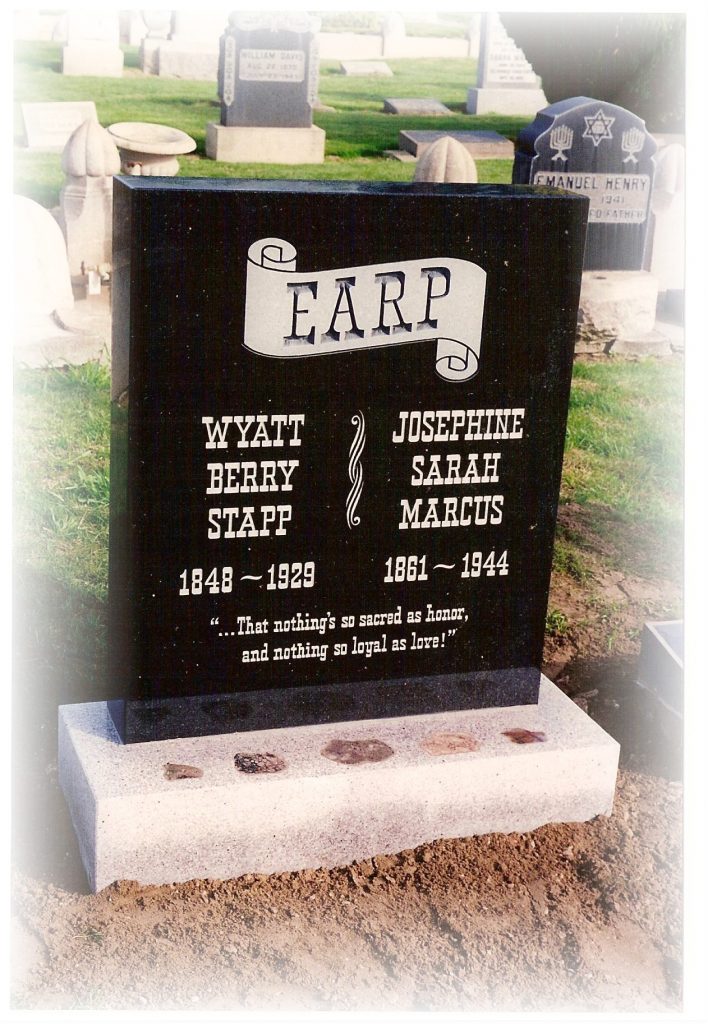

He’s at Hills of Eternity Memorial Park in Colma. Every day at least one, and usually two, people visit the 3-foot-high, black marble headstone perched above the cremated remains of Earp and his wife.

Earp being Earp – i.e., gambler, buffalo hunter and deputy marshal survivor of the 1881 gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Ariz. – those who come leave bullets, poker chips and coins on his grave. But what they leave more often is pebbles – an indicator of one of the least-known facts about the cowboy legend other than the fact that his ashes lie in here. And that is that he is buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Earp is there because his wife, Josephine “Sadie” Marcus Earp, was from a prominent Jewish family in San Francisco. Leaving pebbles on graves is a sign of high respect for the departed in Jewish tradition.

“Wow, I guess he’s still a popular guy,” said 20-year-old Sean Me yers of San Francisco, who came one recent day to take his first view of Earp’s stone. “Look at all that stuff on the grave.”

The stone, which lists both Earp and his wife, bore 38 pennies, a lemon and 17 pebbles. Other than the offerings, though, what surprised Meyers the most was the dates on the marker.

Earp’s dates of life were 1848 to 1929 (making him nearly 81 years old at death) and Marcus’s were 1861 to 1944 (making her 83 at death). We usually expect Wild West figures to predate the 1900s, Meyers mused.

“You know, he never got shot, not even nicked once,” said Meyers, almost reverently. “That’s pretty good for a lawman back in those days. He sure lived a long time. “Who would ever guess he’s here?”